After the sting of betrayal in an abusive relationship, why should we should forgive?

“Forgiveness does not mean forgetting the abuse or pretending that it did not happen. Neither is possible. Forgiveness is not permission to repeat the abuse. Rather, forgiveness means that the victim decides to let go of the experience and move on with greater insight and conviction not to tolerate abuse of any kind again.” (USCCB, “When I Call For Help”)

Forgiveness is an art of giving — of giving to ourselves, to our healing, and to our spiritual growth. It’s letting go of anger and resentment, and dissolving any desire for revenge or payback. It’s a release and a relief.

What forgiveness is not is a memory eraser, nor should it be. “Forgive and forget” is an unhealthy attitude, because it’s impossible to forget excruciating trauma, nor should we try. “Forgetting” in this way is merely burying things rather than healing them — or healing from them.

In order to heal, we can’t avoid our pain. We have to walk directly through the scorching heat of the recovery process.

Even after we fully heal, we won’t magically forget the trauma we’ve endured. Instead we’ll remember it, acknowledge how we’ve grown from the suffering we’ve been through, and recall what the abusive situation was like. This allows us not only to avoid similar situations in the future, but also to feel a healthy sense of much-needed empowerment and self-worth, an acknowledgment of the immense strength it takes to emerge from victim to resilient survivor.

Forgiveness is about release: release of toxic attachment to a situation or person, release of having to dwell on what the person said or did, release to create the space to focus on yourself — on your own God-given strengths and talents, healthy hobbies and pursuits, and the development of close ties with supportive and loving friends and family. Jewel, in her brilliant memoir Never Broken: Songs are Only Half the Story, makes the point that forgiveness “is the scissor that cuts the cord that binds you [and your abuser] together.”

Many survivors have asked me: “Why forgive? He destroyed my sense of self, took away my best years, depleted my spirit. He doesn’t deserve my forgiveness.”

Robert D. Enright is one of the leading psychologists in the field of forgiveness. In his book The Forgiving Life: A Pathway to Overcoming Resentment and Creating a Legacy of Love, he speaks of the necessity of forgiveness and the dangers of harboring resentment by refusing to forgive. When we’ve been betrayed, controlled, and lied to, we naturally recognize either that a love we once had has been taken from us through manipulative betrayal, or that it never truly existed in the way we thought it had.

That hurts. A lot. Lundy Bancroft describes the feeling perfectly:

“The shock to a woman of having her deepest vulnerabilities thrown back in her face by someone she has loved and trusted can cause a burning pain unlike any other. This is intimate psychological cruelty in one of its worst forms.”

After the shock has begun to wear off, feelings of resentment may naturally follow. Dr. Enright describes resentment as something that “sits down in our hearts, takes off its stinky shoes, and makes itself too much at home. After a while, we do not know how to ask it to leave.” It causes us to obsess over negative situations and possibilities and keeps us tied to those who have hurt us in unhealthy ways. Resentment tends to spill over into additional areas of our lives, spreading toxicity within our healthy relationships. We become irritable, impatient, and angry — or exhausted, depressed, and anxious. This creates a ripple effect of isolation and disconnection from others, which makes it difficult to trust anyone, not just the one who actually betrayed us.

When love is broken by betrayal, it has a tendency of breaking everything else, like a terrible tornado directly inside the home.

The cure is forgiveness.

When we’re ready to open ourselves to forgiveness, the path of love will show us how to trust again.

At this point along the journey of forgiveness, however, the focus on regaining trust isn’t on trusting the abuser — something that very well may never be justified — but rather on learning to trust ourselves again. All of us who have been betrayed by abuse have lost not only the gift of trusting our partner and by extension others, but of trusting ourselves. And that is very sad indeed.

Process your anger: anger is healthy and healing.

Embrace it, don’t deny it.

Many people feel stuck because they want to forgive and learn to trust again (regardless of whether or not they want to reconcile), but they still feel angry with their abuser, and perhaps even resentful toward what he’s done and how he’s controlled their life for so long. They’re not sure how to move forward.

The way forward is to recognize those feelings. Embrace them. Love them, even. They’re valid.

Anger isn’t a bad thing. In fact, it can be quite healthy — as long as it’s admitted and processed. Targets of domestic abuse tend to deny anger, believing they’re hurt and heartbroken (which they are) but not necessarily angry (which they most often are, and rightfully so). We need to admit this. Anger is good, as long as it’s kept in a healthy balance. It’s part of the glorious scenery along the path to healing. The CCC mentions anger as one of the “passions” which “are natural components of the human psyche … Passions are morally good when they contribute to a good action; evil in the opposite case” (CCC 1764, 1768).

Being angry about the right things and in the right way is virtuous. But avoiding anger at all times may be a sign of weakness. St. Thomas Aquinas notes how it is a vice not to get angry over things one should. He calls it “unreasonable patience.”

What is the role of anger in forgiveness? How do we use healthy anger to propel us toward self-growth while avoiding the fatal trap of falling into toxic resentment?

It’s all about obsession. Those who feel toxic resentment obsess over past hurts and luxuriate in being a victim.

This is done for a variety of reasons: because it makes them feel as if they have an excuse for their own negative behaviors, because it helps them to avoid feelings of toxic shame, because it gains them the attention of other people’s empathy.

Or, obsessing over past hurts can be a form of dreaming for revenge or “karma” to take its toll on the one who hurt us. None of these attitudes are healthy — and they won’t make us into an authentic, whole person. Only the release of forgiveness can do that.

Yet forgiveness doesn’t equal reconciliation.

Forgiveness and reconciliation are two completely separate issues, and to confuse them would be detrimental and damaging. Forgiveness also doesn’t mean toleration of abusive behavior.

It’s also important to realize that forgiveness isn’t a one-time event. It’s a process, and often a slow one. To force or coerce a false sense of forgiveness because you feel “it’s the right thing to do” is actually the wrong thing to do.

Acknowledge each emotion as it comes.

During the grieving and healing process after domestic abuse, many emotions will arise, subside, arise again, and swirl together. Take each one as they show up, and honour it as a welcome piece in the recovery process. Process your trauma through prayer and self-understanding. Allow forgiveness to eventually flow in a natural, soft way. It will, it just may take time.

The above post was written by Jenny duBay. She is an author, domestic abuse survivor-turned-advocate, and founder of Create Soul Space (https://www.createsoulspace.net).

Find hope in your darkest hour.

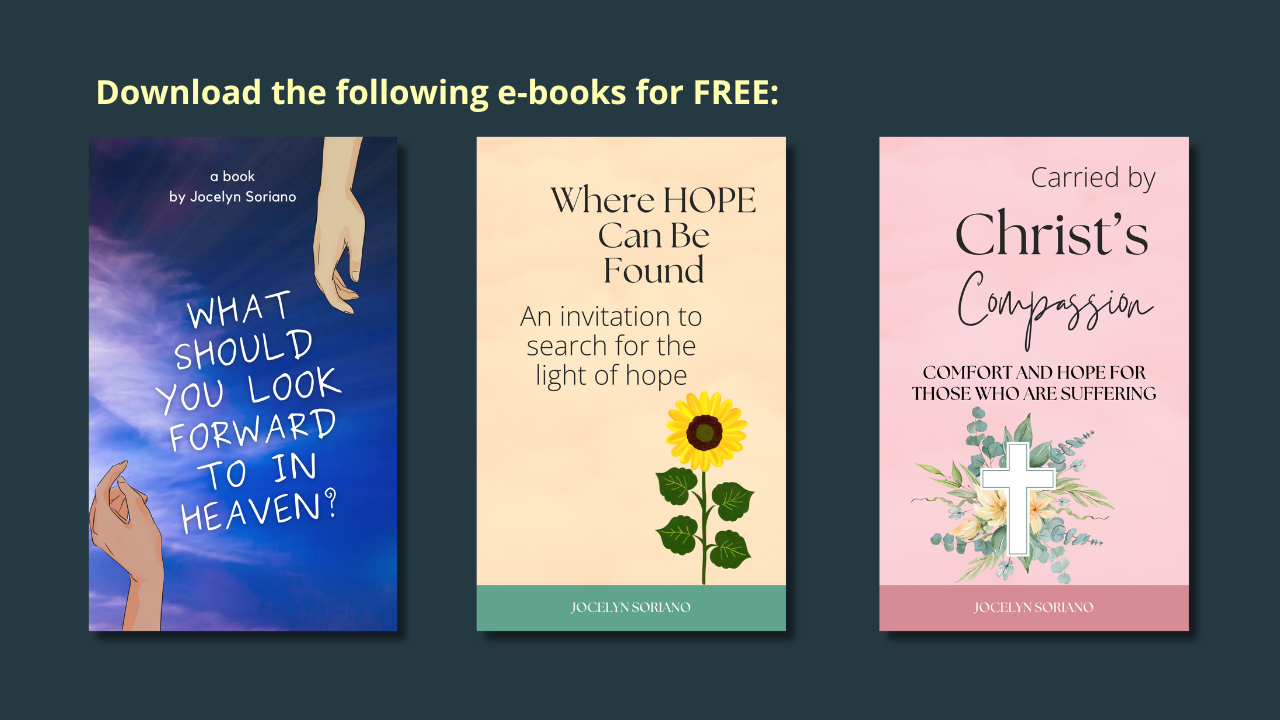

"Download e-books"

Find hope in your darkest hour.

"Download e-books"